Q: What buffer should I use when I want to optimize the pH of the mobile phase? I normally use phosphate buffer, but I heard that phosphate may not always work. How can this be? I thought that phosphate was a great buffer for reversed-phase HPLC. Can you clarify this?

A: Phosphate buffer is the most widely used buffer for reversed-phase HPLC mobile phases. It buffers well, is easy to work with, and has good UV transparency for low-wavelength work. However, it doesn’t buffer well over the entire range that may be needed for reversed-phase methods, and because it is not volatile, it won’t work if you are working with LC-MS or are using one of the evaporative detectors, such as the evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD) or charged aerosol detector (CAD).

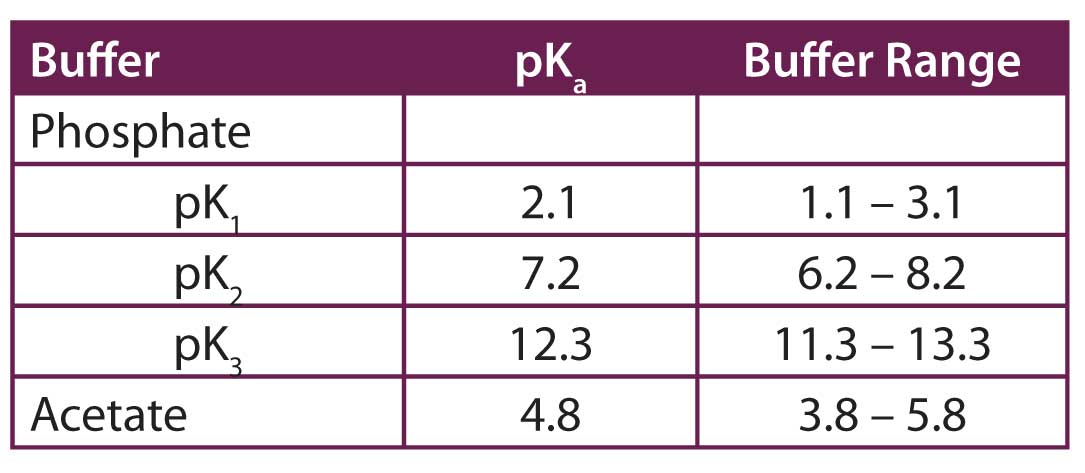

Let’s take a moment and look at buffers in general. From your introductory chemistry class, you’ll remember that a buffer is most effective within ±1 pH unit from its pKa. You can see in table above that phosphate has three different pKa values: 2.1, 7.2 and 12.3. We can discount the 12.3 pKa, because most silica-based reversed-phase HPLC columns are not very stable above pH 8. Also, the bonded phase on reversed-phase columns tends to hydrolyse at pH < 2.0, so that is our lower limit for most purposes. This leaves phosphate with useful buffering regions of 2.0 ≤ pH ≤ 3.1 and 6.2 ≤ pH ≤ 8.0. As long as the mobile phase is within one of these ranges, phosphate will be an effective buffer. But if we want a mobile phase at other pH values, phosphate is not a very good buffer. This means that if we need to run the system at pH 4.0 or 5.0, we’re out of luck with phosphate. Yes, we can adjust the buffer to achieve a pH of 4.0 or 5.0, but there is very little buffering capacity. It is much better to select a buffer that is effective in the pH region that we are interested in using. For example, at pH 4.0 or 5.0, acetate is a good choice. In the table above, you can see that with a pKa of 4.8, acetate is a good buffer in the 3.8 ≤ pH ≤ 5.8.

So what do you do in the case where you want to explore pH as a variable during method development? You could start with phosphate at low pH, then switch to acetate at intermediate pH, and then back to phosphate for the high pH region and cover the entire 2.0 ≤ pH ≤ 8.0 range. Another trick that makes life a little easier is to blend phosphate and acetate together in a single “universal” buffer. For example, you could make up a solution containing 20 mM phosphate and 20 mM acetate and adjust the pH to the desired value over the entire 2.0 ≤ pH ≤8.0 range. (I wouldn’t worry that this stretches the recommended buffering ranges for phosphate and acetate a little in order to cover the 3.1 < pH < 3.8 and 5.8 < pH < 6.2 gaps).

Now you have a buffer that can be used over the entire pH range for stable column operation and you can vary it continuously to allow you to fine-tune the pH. Once you find the best pH for your method, you can drop the unneeded buffer. For example, if the mobile phase pH is 2.8, you can see from Table above that phosphate is doing the work, so acetate can be dropped from the buffer so as to simplify the mobile phase. Similarly, if pH-4.5 is best, use acetate and drop the phosphate. Finally, just a reminder that you need to adjust the pH of the mobile phase in the aqueous portion only, not after adding the organic solvent.